Hardback, 320 pages, John Murray Publishers

(July 2009), ISBN: 9780719597909. Available in good bookshops and from Amazon.co.uk, Waterstones.com, and Play.com. RRP: £20.

PRAISE FOR ‘ALONG THE ENCHANTED WAY’

“This is a wild and captivating storyâ€

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, The Sunday Telegraph

“Blacker is an acute observer and he writes very wellâ€

– John de Falbe, The Spectator

“A lyrical description of an almost vanished way of lifeâ€

– Wendell Steavenson, The Sunday Times

Synopsis

Across the snow-bound passes of Northern Romania there is an almost medieval world. Life there is ruled by the slow cycle of the seasons, far from the frantic rush of modern life in every sense.

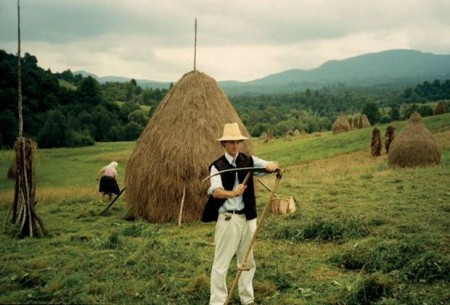

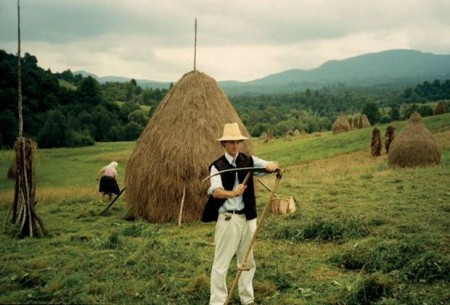

William Blacker lived side-by-side with the amazing people of Romania for many years, having accidentally stumbled upon this hidden universe. In Spring, as the pear trees blossomed, he ploughed with horses. In Summer he scythed the meadows and during the freezing winters he gathered wood by sleigh. By becoming part of this small, close community, Blacker was accepted into the community.

The Gypsies of Romania have always held particular fascination for the few travellers who venture into such remote parts of the world. They are considered untrustworthy, disliked and feared by the local villagers. Blacker was intrigued – and eventually fell in love with a Gypsy girl.

Change is afoot in rural Romania. William Blacker’s adventures in this fascinating country will soon be embedded in world history. From his carefree early days, tramping the hills of Transylvania to the book’s poignant ending, Along the Enchanted Way transports us back to a time many of us thought had all but vanished.

WIN ONE OF THREE COPIES OF ‘ALONG THE ENCHANTED WAY’!

To celebrate the launch of this book, the Romanian Cultural Centre in London has teamed up with John Murray Publishers in order to offer three readers the chance to win a copy of ‘Along the Enchanted Way’.

All you have to do is to provide the answer to this question: What is the name of the traditional drink specific to Maramures?

Hint: the attentive reader will see it mentioned further on in this message.

Send your replies by Thursday 1 October 2009 at mail@romanianculturalcentre.org.uk . Don’t forget to include in your message your FULL NAME and a TELEPHONE NUMBER where we can contact you. The winners will be selected through a raffle from all the correct answers received by the end of 1 October 2009, and will be notified in writing at the e-mail address provided.

Please note that the books won in this contest can be delivered free of charge to UK addresses only.

William Blacker lived in Romania from 1996 to 2004. He has contributed articles to various newspapers and magazines including the Daily Telegraph, Times, Ecologist and Art newspaper. He now divides his time between England, Romania and Italy. He has a child who lives in Romania. As a treat to our readership, William gave an interview to the Romanian Cultural Centre recently, which we present below. The Romanian version, translated from the English by Mihai Risnoveanu, was published in the August edition of “Timpul†cultural magazine from Iasi, Romania (on page 13). A PDF copy can be downloaded from www.timpul.ro/magazines/82.pdf .

Image above: William Blacker in Maramures, at the time of haymaking. Photo © William Blacker, courtesy of John Murray Publishers

INTERVIEW WITH WILLIAM BLACKER

by Ramona Mitrica, Director, Ratiu Foundation / Romanian Cultural Centre

Ramona Mitrica: First of all, congratulations for publishing ‘Along the Enchanted Way’. It is a wonderful book, with all the right ingredients that make for excellent reading: journeys of discovery, danger, passion, and horse-driven carts.

The action is set entirely in Romania, and it is a personal account of your life there. How much poetic licence did you take while writing it?

William Blacker: A lot less than some readers may think. Life in the Maramures when I first went there was very much as I described. The people lived almost entirely pastoral lives, such as those written about by Tolstoy or Hardy. Perhaps occasionally I did observe their world through 'rose-tinted spectacles', or through eyes mildly blurred by swigs of 'horinca', but in general there was no need to exaggerate.

As far as romanticizing the situation of the country people, I would much rather mildly romanticize than err in the other direction and suggest, as others do, that the peasants live in misery and poverty; that would have been both unfair and not at all accurate. For example, in the village of Breb where I stayed for many years most people lived in comfortable houses with large gardens and orchards, and with land for cultivating all the food they needed. When Romanians come to England they are appalled to see the conditions in which many English people live, in what seem to them to be tiny box-like houses all in a row, with even tinier gardens.

In the village my time was spent on the hills, in the hay meadows and the forests. I worked side by side with the villagers almost everyday, and became immersed in their traditional way of living. The people’s almost unfailing good-humour and easy manner made me sure that their lives were as contented and fulfilled as anyone’s.

RM: At a point in the book, you say that Romania “seemed like the wing of a mansion which had been closed up for a hundred yearsâ€. After almost twenty years since your first visit there, does this description still apply?

WB: Not so much anymore. The modern world has blundered in and, for better or worse, things have changed and are still changing. Nonetheless, anyone visiting the Romanian countryside for the first time will still find it an enchanting place, and there are still many corners of the mansion which remain unexplored.

RM: You are, by all standards, a very good friend of Romania, helping to preserve and restore its heritage. How did you get to be interested in Romania in the first place?

WB: In the late 1980's I had read a few articles in English newspapers about Romania. In particular there was one in 'Country Life' about the painted monasteries of the Bukovina. When I found myself in Prague in early January 1990, and with a car, I remembered the monasteries and decided to head east to visit them. As soon as I entered Romania, I saw what an exceptionally beautiful country it was, and how the people still lived the traditional and harmless way of life, the sort which so many people in the West want to emulate, but find so difficult to achieve. I was sure there was much to see and much to learn, and I was right.

I was also captivated by the beauty of the villages, both by their settings amongst the hills, forests and mountains, as well as by their well-preserved houses and barns. I had read in England of how the villages in Romania were being demolished on the orders of President Ceausescu, and so was enormously relieved to find that they were in fact almost all untouched and more architecturally-intact than any I had seen in all of Eastern Europe.

It was only after 1990 that the damage to these villages really began. Partly because some of the villages were abandoned by their previous inhabitants, party because of rampant and uncontrolled modernization. In an effort to help in 1996 I wrote a pamphlet about the plight of the Saxon villages of Transylvania. Happily, as a result of this little book large sums of money were raised to help preserve Romanian architecture. Most has been donated by the Packard Humanities Trust, and I am immensely grateful to them for their kindness and for the support of David Packard for Romanian architecture. There still, however, remains much to be done. It is vital that there are effective laws to protect historic buildings. At the moment the laws are not effective. Old buildings are being destroyed at an alarming rate. If this continues large swathes of the visual part of Romania’s history will be rubbed out. This would be a tragedy for Romania, as historic buildings can never be replaced. Romania wishes to be considered a modern country but modern countries protect their historic architecture.

RM: From reading the book, anyone can see that you bear a deep love for the Romanian countryside. What made you develop this passion to the point you lived there for some very good years? What was it like to live “off the fruit of the landâ€, just like a Romanian peasant?

WB: I had always loved the country, especially in England and Italy. Then, when I first visited Romania I was very happy to have found a place even more beautiful, and where the country people were more ‘alive’, and more involved with the natural world than in the West.

Concerning self-sufficiency - In the Maramures I was looked after by Mihai and Maria, they fed and housed me, and in return I helped them by working in the fields, the orchards, the woods and the distillery. We lived entirely off what we produced. Only sugar was bought. There was a great satisfaction in walking home tired from the fields in the evening, along the small paths, with our scythes, forks and rakes over our shoulders, chatting and exchanging jokes with other villagers. Everyone knew that on that day they had made a small step towards providing themselves with the food they needed for the year. I could not complete even half the work that the villagers could, but I felt a part of their lives, and I sensed that the hard work required in sun, rain and snow gave everyone a bond and a common purpose.

RM: You describe in the book episodes of rustic charm, but you haven’t shied away from presenting the troubled side of things, as well, things you lived through.

WB: Yes. I was just telling the story of my years there. I did not think it right to brush the unpleasant things under the carpet and pretend they never happened. Certainly some of the things Marishka and I experienced were upsetting, and sometimes hard to bear, but I was helped by many kind people, and I am glad to say life is now a lot easier.

RM: There are many people, both British and Romanians, who will be envious of the “simple life†you led, and many who would ask themselves “why did he go to live there, when many seem just to want to leave�

WB: Indeed, I could never understand why there were not more foreigners living in Romania. For me it seemed the only place to be.

At the same time I found it difficult to understand why so many Romanians wished to leave, but equally I knew that I was in a privileged position. The pound was strong and went a long way in those days. I loved being there, but I understood why many Romanians wanted to go to earn better money abroad. It was very sad to see them go, and sad to see the way of life in the villages changing, but it was inevitable.

RM: You describe in your book, besides life in Maramures, life in a Saxon village where you settled. You also describe meeting the Roma Gypsy in Transylvania. I read your article in The Times ‘The Roma: Why we shouldn’t fear Gypsies’. Without giving any of the book away, can you please tell us what your involvement with this particular community was?

WB: I lived for some years with a Gypsy girl from a family of musicians. It was a delightful if slightly stormy period in my life. While living with her I worked with many Gypsies from the surrounding villages. They were skilful craftsmen and did much vital work repairing and preserving historic houses in Romania.

RM: And finally, what compelled you to write this story, and have you any plans for a follow-up?

WB: I saw that I was in the rare position of being a traveller from the late 20th century witnessing, day by day, life in a land which was in many respects just emerging from the Middle Ages. When I talked to people from England and Italy about my experiences, they always longed to know more.

And yes, I would like to write other books. I might write more about the Maramures; I certainly have plenty of material.