Monday 15 September 2008, 7.30 pm

Wigmore Hall, 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP, Tel. 020 7935 2141

Tickets: £15.00 £13.00 £10.00 £8.00

How to Book

- In person: 7 days a week; 10am – 8.30pm. Days without an evening concert 10am – 5pm. No advanced booking in the half hour prior to a concert.

- By telephone: 020 7935 2141. 7 days a week; 10am – 7pm. Days without an evening concert; 10am – 5pm. There is a £1.50 administration fee for all telephone bookings which includes the return of your tickets by first class post.

- Online: http://www.wigmore-hall.org.uk/whats-on/productions/remus-azoitei-violin-22197. 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a 50p administration fee for online bookings, which includes the return of your tickets by first class post.

- Facilities for Disabled People: Please contact House Management, tel: 020 7258 8210, for full details.

Programme

George ENESCU, (1881-1955)

Impressions d’enfance, op. 28 (1940)

(Impressions of Childhood)

- The fiddler

- An old beggar

- The stream at the bottom of the garden

- The caged bird and the cuckoo clock

- Lullaby

- A cricket

- Moonlight through the window

- Wind in the chimney

- Storm outside, in the night

- Sunrise

Johannes BRAHMS, (1833-1897)

Sonata in D minor, op. 108 (1888)

- Allegro

- Adagio

- Un poco presto e con sentimento

- Presto agitato

interval 20 minutes

George ENESCU

Impromptu Concertant (1903)

Johannes BRAHMS

Scherzo from “FAE Sonata” (1853)

George ENESCU

Sonata no. 3 “in Romanian Folk Character”, op. 25 (1926)

- Moderato malinconico

- Andante sostenuto e misterioso

- Allegro con brio, ma non troppo mosso

Introduction from Mr Nicolae Ratiu, Chairman of the Ratiu Foundation

“The Ratiu Foundation is proud to present tonight’s concert, and most of all we are proud to see our friend Remus Azoitei on this prestigious stage, performing the immortal music of Enescu and Brahms.

The Ratiu Foundation was established in 1979 by Ion and Elisabeth Ratiu in order to promote and support projects which further education and research in the culture and history of Romania and its people. More details on http://www.ratiufamilyfoundation.com

Throughout the years, the Foundation has been honoured to put its wholehearted support behind a multitude of Romanian musicians, including many young, extremely talented and very promising individuals. As I am sure you will agree, our backing is returned tenfold by the successes of the music projects and musicians which we funded – as in the case of Remus, whom the Foundation embraced and supported from his arrival in Britain.

I would like to thank both Remus Azoitei and Eduard Stan for their tireless work to promote Enescu's music. Their CD recordings of Enescu’s works for violin and piano, which the Foundation also supported, garnered critical acclaim and furthered awareness of George Enescu, who is regarded by Romanians as their national composer. Although Enescu already has many admirers, his oeuvre deserves to be better known in Britain. That is why we believe it was not only a pleasure to be able to organise this concert, but also a duty. I am sure you will enjoy this unique programme of works by Enescu and Brahms, and I trust you will leave tonight under the spell of the two master composers as, brought to life by these two most gifted musicians: Remus Azoitei and Eduard Stan.”

Introduction from Ms Ramona Mitrica, Director of the Ratiu Foundation / Romanian Cultural Centre in London

“I am sure you have your own mental image of Romania: perhaps to you it is a country characterised by some of the most impressive landscapes in Europe; or a place you visited as a tourist but returned as a friend. Maybe you know of Romania through some of its more famous denizens who are or were (not necessarily in order of importance) Dracula, Hagi, Ceausescu, Nadia Comaneci and the Cheeky Girls.

What many people do not know is that Romanian culture is as diverse and impressive as its landscapes and that some of its cultural figures deserve to stand alongside the names of artists, musicians and composers with whom you will be more familiar.

Tonight’s concert, and the work of the Romanian Cultural Centre (RCC) in London more generally, are attempts to redress this. The Centre seeks ways to promote Romanian culture, in partnership with others, and through the efforts of Romanian artists.

Our goal is to make British audiences aware of the depth and diversity of our cultural heritage, and the talents of those with Romanian roots. If we can interest concert halls, galleries, and the general public in these works, we hope this will generate the demand to see more. With the virtuosity on display at Wigmore Hall tonight, I believe we cannot go wrong. I hope also that when you leave here tonight there will be two more Romanian names added to the top of your list, artists who show there is so much more to Romania than a dead dictator, an un-dead Count, two sportspeople, and some very cheeky girls.

Listen with attention and with all your heart to this evening’s concert, and, through the masterly sounds of Remus Azoitei and Eduard Stan, as well as through Enescu’s chords we offer you a glimpse of the inner-most soul of Romania.”

PROGRAMME NOTES: BRAHMS AND ENESCU

The richness of Vienna’s musical history is such that sometimes moments that would dominate in other less fortunate surroundings have almost been forgotten.

The meeting of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) and George Enescu (1881-1955) – two defining representatives of quite different cultural traditions – is one such moment, though we do not know exactly when this happened. By the time Enescu was admitted to the Vienna Conservatoire, principally to study the violin in 1888 at the age of seven, Brahms was well established in the city having lived there for twenty years and furthered his reputation as a composer.

Brahms regularly conducted student orchestras and under his baton Enescu played works by Mendelssohn, Sarasate and Brahms’s own first symphony. Enescu also claimed to have received advice on playing the cadenza for Brahms’s violin concerto from the composer.

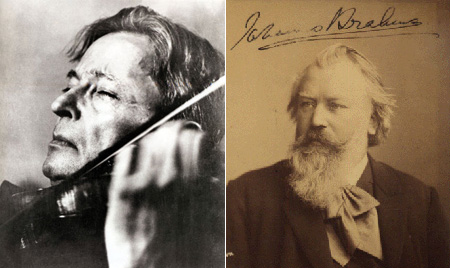

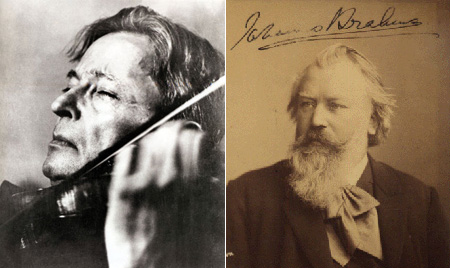

Left: George Enescu, promotional photograph. Evan Dickerson's private collection. Right: Johannes Brahms.

Left: George Enescu, promotional photograph. Evan Dickerson's private collection. Right: Johannes Brahms.

By the time Enescu moved to Paris in 1895 to continue his studies he had completed three overtures in Wagnerian style, a clutch of works for piano, tried his hand at string quartets and felt himself ready to compose symphonies. The first two of four ‘school’ symphonies quickly followed, clearly displaying the influence of Brahms’s mature style on the young composer. Enescu stated when interviewed in 1951, “I passionately liked Brahms’s music; I listened with profound emotion not only because I found it admirable, but also because it evoked my homeland for me.” The inference is that he intended a homeland not defined in geography but of personal, emotional and musical connections. Eduard Stan, tonight’s pianist, reinforces the point: “For me it is obvious that Enescu acquired his love of chamber music from Brahms, both in terms of form – sonatas, trios, piano quartets, etc. – and sonority there are many similarities at a fundamental level.”

By 1940 when Enescu wrote his most complex late duo work, Impressions d’enfance, his health was declining through a combination of heart problems and the worsening of a gradually crippling spinal condition. Despite this he was forced by financial necessity to undertake engagements as a violinist, pianist, conductor and teacher when his only desire was to compose and be in Romania. But within a few years later he went into self-imposed exile in Paris due to the war.

Another poignant association, which links itself all too easily with the work, is the account left to us by Romeo Drãghici of Enescu’s final visit to his childhood home at Liveni in northern Moldavia. Drãghici recalled that, “Enescu asked to be left alone to go into the garden at the back of the house. On his return he was depressed and melancholy. … He went next to the graveyard in Dorohoi where his father lay buried, and then to his mother’s grave at Mihaileni where he was visibly shaken by emotion.”

The ten fleeting distant reminiscences of childhood that constitute Impressions d’enfance are as evocative in their imagery as they are powerful in their musical language.

The fiddler, for solo violin, evokes the instinctive performance of a Moldavian street fiddler, though the thematic material is of Enescu’s creation rather than being authentic.

An old beggar is touchingly characterized, the violin part being marked with indications such as ‘a little hoarsely, but soft and sad’ to bring out the quality of the beggar’s voice.

The stream at the bottom of the garden is a recollection from Enescu’s childhood: he related “I can still see it – the stream which ran softly at the bottom of our garden – and sometimes it grew into a little pond which shimmered in the light…” The caged bird and the cuckoo clock takes us into the house to capture the stark differences between their songs, with the mechanism of the cuckoo clock represented in the piano part. Lullaby presents a challenge for the players with its delicate unison scoring and exactness of tempo to produce the impression of a mother singing to her child.

A cricket, for all its brevity, effectively mimics the subtle sound heard through an open window. Moonlight through the window carries the nocturnal scene further before one of the most imaginative passages of all Enescu’s writing, Wind in the chimney. This, however, is just the prelude to Storm outside, in the night which follows without a break. It gathers pace and ferocious energy before breaking into the climactic closing Sunrise, which Enescu intends not only as a literal representation but as a vision of destiny, pulling him away from his past back, to the present, and towards a future that cannot be escaped.

Brahms’s third violin sonata is the only one written in four movements. Completed during his summer holiday in 1888 at Lake Thun north of the Swiss Alps, the work is dedicated to the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow.

As with the earlier sonatas Brahms sets the atmosphere in the opening bars, finding an almost symphonic sense of scale combined with the heroic passion of his youthful piano sonatas.

The violin part opens with a sinuous theme, the full intensity of which is only suggested at first. A seeming lack of natural rhythm is further heightened by the sforzandos on the weak beats and the piano’s right hand syncopation.

The heart of the movement is the development section, which is built entirely over a pedalled fifth which seems in constant contrast to the shifting harmonics played over it.

The second movement Adagio in D major provides the only escape from minor keys but maintains its intensity by largely confining itself to the lower and middle registers. The third movement is more openly playful and nervous, despite its brevity.

The final Presto agitato gives the work a sense of balance, as it counterpoints the passion of the first movement by presenting an argument of conflicting emotions, with the exuberant first theme neatly foiled by the more tranquil material of the second theme. Schoenberg later credited this movement as being the inspiration for him to invent the twelve-tone system, such is the feeling of free association between the thematic material.

The Impromptu Concertant is one of several short concert pieces that Enescu wrote for a variety of instruments throughout his life. Dating from 1903, the effusiveness of Enescu’s youthful style is undeniably a major feature of the piece. That it was published posthumously in 1958 also tells us something of Enescu’s self-criticism regarding even the smallest elements of his oeuvre.

The character of this spontaneous work is captured in the eloquent instruction that prefaces the music, “chaleureux et mouvementé”, with tenderness and moving. Its two connected and distinctive parts enable audiences to appreciate the main influences on Enescu’s compositional development. The first part finds both instruments intertwining their lines in a very Viennese manner that reminds at times of Richard Strauss’s lyricism whilst maintaining a sense of airy freedom. The second part is one of passionate expression for the violin against an accompaniment that draws upon Fauré without negating the influence of Brahms in the prominence given to its chord-based construction.

It is known that Brahms destroyed at least three outlines for violin sonatas before completing the three that finally came into being. The Scherzo from the “F.A.E.” sonata is a survivor from his early attempts at grappling with the form. Rather unusually Brahms wrote the Scherzo in 1853 as a contribution towards a collaborative sonata with the composer Robert Schumann and his pupil Albert Dietrich providing the other movements.

It was Schumann who suggested it be dedicated to the violinist Joseph Joachim. As a further source of amusement the composers kept their identities hidden from Joachim until after he had played through the work, which he did in the Schumann household with Clara Schumann at the piano, and guessed their identities without any difficulty.

The work was unpublished in its entirety during the composers' lifetimes, though Schumann incorporated his two movements into his third violin sonata. Joachim retained the original manuscript, from which he allowed just Brahms’s scherzo to be published in 1906.

This is the only part to have maintained its place in the regular repertoire. As a side note of interest, all three composers wrote a concerto dedicated to Joachim.

“F.A.E.” refers to Joachim’s overtly Romantic personal motto, “Frei aber Einsam” (Free but alone), indicating the solitary lifestyle of the virtuoso artist. Dietrich and Schumann both used the notes F, A and E as integral elements of their themes, but Brahms cast his Scherzo in the somewhat removed key of C minor which lends the writing a sense of uncertainty before leading to a coda in C major, which in turn references A minor, the key of the other movements.

Enescu’s third violin sonata is one of his best-known works. As the subtitle “in Romanian Folk Character” indicates, the work provides a unique distillation of Romanian folk music. Enescu was clear about the specific use of the word ‘character’: “I don’t use the word ‘style’ because that implies something made or artificial, whereas ‘character’ suggests something given and natural. The use of folk material does not ensure authentic folk character, it contributes to it when done with the spirit of the people … and in this way Romanian composers will be able to write authentic music but achieve it through different and personal means.” Rather more personally he stated, “I was born rooted in the earth, in ground full of tales and legends. My whole life took place under the influence of my childhood gods.”

The music reflects both Romania’s history and geographic location as a meeting point between East and West, with the absorption over many years of ingredients from the Hungarian, Slavic, Arabic and Jewish traditions as well as native folk forms. Yehudi Menuhin, Enescu’s pupil, referred to the sonata’s sense of “nostalgia, yearning, resignation and intense sadness”, though its bitter-sweet tinge is best captured in the Romanian word dor.

The first movement, marked Moderato malinconico, immediately brings to mind the spirit of a Romanian doina, through the use of parlando rubato playing which imitates free recitative. Here, as elsewhere, this is achieved by a veritable minefield of markings in the score that the players have to negotiate: precise fingerings, several flavours of glissandi, varied harmonics and minute tempo changes every bar or two.

The pianist Alfred Cortot, who accompanied Enescu in the sonata, characterised the second movement as “evoking the sounds of mysterious summer nights in Romania; down below, the silent, endless, neglected plains; above, stars leading into the infinite…” Indeed, aside from Bartók’s use of night music in his chamber and orchestral works, this is the most stunning example of musical imagination that exists in the duo repertoire. The closing movement builds into a wild dance full of rhapsodic reminiscences further heightened and tinged by the doina form before reaching an exultant end.

Programme notes: Evan Dickerson

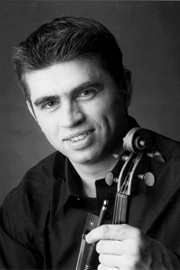

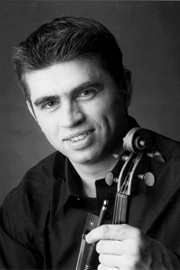

REMUS AZOITEI – VIOLIN

Violinist Remus Azoitei has achieved international acclaim since his concert debut at the age of eight. Since then, he has performed extensively as a soloist with all the major orchestras in Romania, as well as being a featured soloist with other ensembles in Europe, North America and Japan. Hailed as “an uninhibited virtuoso, with soul and fabulous technique” by The Strad, Remus held a full scholarship to study with Itzhak Perlman and Dorothy DeLay at the Juilliard School in New York, where he obtained his Master’s Degree, as well as studying under Maurice Hasson at the Royal Academy of Music in London.

As a recitalist, Remus Azoitei has performed in venues such as the Alice Tully Hall at the Lincoln Center and CAMI Hall (New York), St-Martin-in-the-fields and Wigmore Hall (London), also appearing, among others, at the Music Festivals of Yokosuka, Cambridge, London, Heidelberg, Paris, Santander, Munich and Bucharest. Remus’ works have been broadcast on the Romanian Cultural Channel, BBC Radio 4, Radio Kishinev, as well as on Concert FM in New Zealand. He has worked with artists such as David Geringas, Nigel Kennedy, Gérard Caussé, Adrian Brendel and Konstantin Lifschitz. After his London Wigmore Hall debut in 2004, the Sunday Express wrote that “he delivered a memorable programme in front of a packed Wigmore Hall, and had the crowd cheering. He is one fine musician.” In 2005, he performed the Bach Double concerto with Nigel Kennedy, a concert broadcast by 19 TV and Radio stations across Europe and North America, including Arte and Mezzo. He has recorded for the Electrecord, Radio Bremen, and Hanssler Classics. At the 2009 Enescu Festival, Remus will be a soloist of the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, conducted by Dmitri Kitaenko.

Remus is a prize-winner at international violin competitions in Milan, Weimar, Bucharest and Wellington. In 2005 he received “The Cultural Order”, a decoration awarded by the Romanian President to him for his musical achievements.

In addition to his busy concert schedule, Remus is dedicated to teaching. He was appointed violin professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London in 2001, becoming the youngest ever violin professor in the history of the institution. In 2006, Remus was awarded the title of Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, ARAM. He is the founder of the Enescu Society in London, as well as its Artistic Director. Tonight, he plays on a 1718 Antonio Stradivari violin, the “Maurin”, kindly offered to him for this concert by the Royal Academy of Music.

EDUARD STAN - PIANO

Hailed as an “enormously sensitive pianist with an extraordinary flexible culture of touch, perfect technique as well as a great understanding of music” by the German Weserkurier, Romanian-born Eduard Stan moved to Germany in 1978 at the age of eleven.

After Karl-Heinz Kämmerling noticed his talent, it was Arie Vardi who became Eduard’s main mentor at the Academy of Music and Drama in Hanover, where he obtained his Master’s Degree. Praised by Vardi as “a successful combination of a Romanian soul with musical sensitivity grown on German spiritual ground”, he also benefited from the advice of Herbert Blomstedt, Matthias Goerne, Karl Engel, Boris Berman and Paul Badura-Skoda.

A top prize-winner at international competitions in Cologne, Hamburg and Brunswick, Eduard Stan has appeared at festivals including Massenet (France), Mid-Europe (The Czech Republic), Bourglinster (Luxemburg), Brunswick Classix (Germany) and the Festival of Romanian Music (Romania). He has performed across Europe and the US, including major concerts at the Berlin Philharmonie, Musikhalle Hamburg, Salt Lake City Temple Square and PUC California.

As featured soloist with orchestras in Germany, Austria, Italy and Romania, he performed under baton of Shinya Ozaki, Lutz Köhler, George Balan and Thomas Dorsch, among others. As a sought-after chamber musician revealing “a fine gift of restraint and an instinctive feel for balance” (The Strad), Eduard regularly performs with violinist Remus Azoitei, cellist Laura Buruiana, as well as the Voces and Ad Libitum string quartets, Romania’s leading ensembles.

His affinity for Lied accompaniment is appreciated by singers such as Britta Stallmeister, Sylvia Bleimund, Eliseda Dumitru and Johannes Gaubitz.

Eduard Stan’s critically acclaimed Solo-CDs for Hänssler Classic range from Bach to Debussy. Together with his compatriot Remus Azoitei, he recorded the entire repertoire for violin and piano by George Enescu, a world premiere project coming in two CD volumes, released by Hänssler in 2007.

Eduard Stan has been a teacher at the Lübeck Academy of Music from 2000-2007. As the founder and artistic director of the Enescu-Festival Heidelberg/Mannheim, he was awarded in 2005 the Enescu Medal from the Romanian Cultural Institute for his merits as a promoter of Enescu’s music. Future projects include his debut at Flagey Hall in Bruxelles, the Philharmonie in Luxemburg, as well as a tour Australia and New Zealand in 2009.

REMUS AZOITEI AND EDUARD STAN, THE ENESCU RECORDINGS

In 2007, Remus Azoitei and Eduard Stan, released George Enescu‘s entire repertoire for violin and piano, a world premiere project. Launched by Hanssler Classics on 2 CDs, this collection attracted immediate international acclaim.

American Fanfare Magazine reviews it as “an incandescent reading that positively bursts forth with energy from this genuine musical partnership”, and proposes it as a “strong candidate for admission to the Classical Hall of Fame.” The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung names it a “phenomenal recording”, and the German Ensemble-Magazin for chamber music rated the recording with five stars (their highest possible ranking). The CD is selected by the May edition of the Swiss periodical Musik & Theater as “The Surprise” of the month, while the reviewer is suggesting that “the name of the exemplary interpreters should be retained”.

Classical Source notes that “Azoitei identifies completely with the music. He surmounts the music’s technical challenges with such ease you forget they are there and focus on the music’s eloquent magic”, and The Strad states that “Azoitei has all the requirements: marked sensitivity, a sweetness of tone (but not over-succulence) and an impressive emotional and dynamic range”. The Romanian Actualitatea Muzicala states that “Stan achieves the most special sounds and colours in his playing, from a delicate pianissimo to an organ quality fortissimo, going through all the intermediate dynamics in between.”

Amongst other reviews of the CD the recordings are described as “Interpretational mastery!” (Fono-Forum–Germany), “Assured performance, enthralling reading, a superb disc” (International Record Review), “One can not wish for a more authentic interpretation” (Musik & Theater–Switzerland), “Spectacular performance” (Musika21–Poland), “Grand virtuosity” (La Scena Musicale – Canada). The International Record Review remarks it is: “In short, a superb disc that makes the second volume the more keenly awaited”. The Strad concluded its review with “Hänssler has done this recording proud: every detail is caught to perfection”.

Composers’ photos from the public domain (the European Union, Canada, USA as well as other countries). Photo of George Enescu performing courtesy of Evan Dickerson, from his private collection.

Left: George Enescu, promotional photograph. Evan Dickerson's private collection. Right: Johannes Brahms.

By the time Enescu moved to Paris in 1895 to continue his studies he had completed three overtures in Wagnerian style, a clutch of works for piano, tried his hand at string quartets and felt himself ready to compose symphonies. The first two of four ‘school’ symphonies quickly followed, clearly displaying the influence of Brahms’s mature style on the young composer. Enescu stated when interviewed in 1951, “I passionately liked Brahms’s music; I listened with profound emotion not only because I found it admirable, but also because it evoked my homeland for me.” The inference is that he intended a homeland not defined in geography but of personal, emotional and musical connections. Eduard Stan, tonight’s pianist, reinforces the point: “For me it is obvious that Enescu acquired his love of chamber music from Brahms, both in terms of form – sonatas, trios, piano quartets, etc. – and sonority there are many similarities at a fundamental level.”

By 1940 when Enescu wrote his most complex late duo work, Impressions d’enfance, his health was declining through a combination of heart problems and the worsening of a gradually crippling spinal condition. Despite this he was forced by financial necessity to undertake engagements as a violinist, pianist, conductor and teacher when his only desire was to compose and be in Romania. But within a few years later he went into self-imposed exile in Paris due to the war.

Another poignant association, which links itself all too easily with the work, is the account left to us by Romeo Drãghici of Enescu’s final visit to his childhood home at Liveni in northern Moldavia. Drãghici recalled that, “Enescu asked to be left alone to go into the garden at the back of the house. On his return he was depressed and melancholy. … He went next to the graveyard in Dorohoi where his father lay buried, and then to his mother’s grave at Mihaileni where he was visibly shaken by emotion.”

The ten fleeting distant reminiscences of childhood that constitute Impressions d’enfance are as evocative in their imagery as they are powerful in their musical language.

The fiddler, for solo violin, evokes the instinctive performance of a Moldavian street fiddler, though the thematic material is of Enescu’s creation rather than being authentic.

An old beggar is touchingly characterized, the violin part being marked with indications such as ‘a little hoarsely, but soft and sad’ to bring out the quality of the beggar’s voice.

The stream at the bottom of the garden is a recollection from Enescu’s childhood: he related “I can still see it – the stream which ran softly at the bottom of our garden – and sometimes it grew into a little pond which shimmered in the light…” The caged bird and the cuckoo clock takes us into the house to capture the stark differences between their songs, with the mechanism of the cuckoo clock represented in the piano part. Lullaby presents a challenge for the players with its delicate unison scoring and exactness of tempo to produce the impression of a mother singing to her child.

A cricket, for all its brevity, effectively mimics the subtle sound heard through an open window. Moonlight through the window carries the nocturnal scene further before one of the most imaginative passages of all Enescu’s writing, Wind in the chimney. This, however, is just the prelude to Storm outside, in the night which follows without a break. It gathers pace and ferocious energy before breaking into the climactic closing Sunrise, which Enescu intends not only as a literal representation but as a vision of destiny, pulling him away from his past back, to the present, and towards a future that cannot be escaped.

Brahms’s third violin sonata is the only one written in four movements. Completed during his summer holiday in 1888 at Lake Thun north of the Swiss Alps, the work is dedicated to the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow.

As with the earlier sonatas Brahms sets the atmosphere in the opening bars, finding an almost symphonic sense of scale combined with the heroic passion of his youthful piano sonatas.

The violin part opens with a sinuous theme, the full intensity of which is only suggested at first. A seeming lack of natural rhythm is further heightened by the sforzandos on the weak beats and the piano’s right hand syncopation.

The heart of the movement is the development section, which is built entirely over a pedalled fifth which seems in constant contrast to the shifting harmonics played over it.

The second movement Adagio in D major provides the only escape from minor keys but maintains its intensity by largely confining itself to the lower and middle registers. The third movement is more openly playful and nervous, despite its brevity.

The final Presto agitato gives the work a sense of balance, as it counterpoints the passion of the first movement by presenting an argument of conflicting emotions, with the exuberant first theme neatly foiled by the more tranquil material of the second theme. Schoenberg later credited this movement as being the inspiration for him to invent the twelve-tone system, such is the feeling of free association between the thematic material.

The Impromptu Concertant is one of several short concert pieces that Enescu wrote for a variety of instruments throughout his life. Dating from 1903, the effusiveness of Enescu’s youthful style is undeniably a major feature of the piece. That it was published posthumously in 1958 also tells us something of Enescu’s self-criticism regarding even the smallest elements of his oeuvre.

The character of this spontaneous work is captured in the eloquent instruction that prefaces the music, “chaleureux et mouvementé”, with tenderness and moving. Its two connected and distinctive parts enable audiences to appreciate the main influences on Enescu’s compositional development. The first part finds both instruments intertwining their lines in a very Viennese manner that reminds at times of Richard Strauss’s lyricism whilst maintaining a sense of airy freedom. The second part is one of passionate expression for the violin against an accompaniment that draws upon Fauré without negating the influence of Brahms in the prominence given to its chord-based construction.

It is known that Brahms destroyed at least three outlines for violin sonatas before completing the three that finally came into being. The Scherzo from the “F.A.E.” sonata is a survivor from his early attempts at grappling with the form. Rather unusually Brahms wrote the Scherzo in 1853 as a contribution towards a collaborative sonata with the composer Robert Schumann and his pupil Albert Dietrich providing the other movements.

It was Schumann who suggested it be dedicated to the violinist Joseph Joachim. As a further source of amusement the composers kept their identities hidden from Joachim until after he had played through the work, which he did in the Schumann household with Clara Schumann at the piano, and guessed their identities without any difficulty.

The work was unpublished in its entirety during the composers' lifetimes, though Schumann incorporated his two movements into his third violin sonata. Joachim retained the original manuscript, from which he allowed just Brahms’s scherzo to be published in 1906.

This is the only part to have maintained its place in the regular repertoire. As a side note of interest, all three composers wrote a concerto dedicated to Joachim.

“F.A.E.” refers to Joachim’s overtly Romantic personal motto, “Frei aber Einsam” (Free but alone), indicating the solitary lifestyle of the virtuoso artist. Dietrich and Schumann both used the notes F, A and E as integral elements of their themes, but Brahms cast his Scherzo in the somewhat removed key of C minor which lends the writing a sense of uncertainty before leading to a coda in C major, which in turn references A minor, the key of the other movements.

Enescu’s third violin sonata is one of his best-known works. As the subtitle “in Romanian Folk Character” indicates, the work provides a unique distillation of Romanian folk music. Enescu was clear about the specific use of the word ‘character’: “I don’t use the word ‘style’ because that implies something made or artificial, whereas ‘character’ suggests something given and natural. The use of folk material does not ensure authentic folk character, it contributes to it when done with the spirit of the people … and in this way Romanian composers will be able to write authentic music but achieve it through different and personal means.” Rather more personally he stated, “I was born rooted in the earth, in ground full of tales and legends. My whole life took place under the influence of my childhood gods.”

The music reflects both Romania’s history and geographic location as a meeting point between East and West, with the absorption over many years of ingredients from the Hungarian, Slavic, Arabic and Jewish traditions as well as native folk forms. Yehudi Menuhin, Enescu’s pupil, referred to the sonata’s sense of “nostalgia, yearning, resignation and intense sadness”, though its bitter-sweet tinge is best captured in the Romanian word dor.

The first movement, marked Moderato malinconico, immediately brings to mind the spirit of a Romanian doina, through the use of parlando rubato playing which imitates free recitative. Here, as elsewhere, this is achieved by a veritable minefield of markings in the score that the players have to negotiate: precise fingerings, several flavours of glissandi, varied harmonics and minute tempo changes every bar or two.

The pianist Alfred Cortot, who accompanied Enescu in the sonata, characterised the second movement as “evoking the sounds of mysterious summer nights in Romania; down below, the silent, endless, neglected plains; above, stars leading into the infinite…” Indeed, aside from Bartók’s use of night music in his chamber and orchestral works, this is the most stunning example of musical imagination that exists in the duo repertoire. The closing movement builds into a wild dance full of rhapsodic reminiscences further heightened and tinged by the doina form before reaching an exultant end.

Programme notes: Evan Dickerson

Left: George Enescu, promotional photograph. Evan Dickerson's private collection. Right: Johannes Brahms.

By the time Enescu moved to Paris in 1895 to continue his studies he had completed three overtures in Wagnerian style, a clutch of works for piano, tried his hand at string quartets and felt himself ready to compose symphonies. The first two of four ‘school’ symphonies quickly followed, clearly displaying the influence of Brahms’s mature style on the young composer. Enescu stated when interviewed in 1951, “I passionately liked Brahms’s music; I listened with profound emotion not only because I found it admirable, but also because it evoked my homeland for me.” The inference is that he intended a homeland not defined in geography but of personal, emotional and musical connections. Eduard Stan, tonight’s pianist, reinforces the point: “For me it is obvious that Enescu acquired his love of chamber music from Brahms, both in terms of form – sonatas, trios, piano quartets, etc. – and sonority there are many similarities at a fundamental level.”

By 1940 when Enescu wrote his most complex late duo work, Impressions d’enfance, his health was declining through a combination of heart problems and the worsening of a gradually crippling spinal condition. Despite this he was forced by financial necessity to undertake engagements as a violinist, pianist, conductor and teacher when his only desire was to compose and be in Romania. But within a few years later he went into self-imposed exile in Paris due to the war.

Another poignant association, which links itself all too easily with the work, is the account left to us by Romeo Drãghici of Enescu’s final visit to his childhood home at Liveni in northern Moldavia. Drãghici recalled that, “Enescu asked to be left alone to go into the garden at the back of the house. On his return he was depressed and melancholy. … He went next to the graveyard in Dorohoi where his father lay buried, and then to his mother’s grave at Mihaileni where he was visibly shaken by emotion.”

The ten fleeting distant reminiscences of childhood that constitute Impressions d’enfance are as evocative in their imagery as they are powerful in their musical language.

The fiddler, for solo violin, evokes the instinctive performance of a Moldavian street fiddler, though the thematic material is of Enescu’s creation rather than being authentic.

An old beggar is touchingly characterized, the violin part being marked with indications such as ‘a little hoarsely, but soft and sad’ to bring out the quality of the beggar’s voice.

The stream at the bottom of the garden is a recollection from Enescu’s childhood: he related “I can still see it – the stream which ran softly at the bottom of our garden – and sometimes it grew into a little pond which shimmered in the light…” The caged bird and the cuckoo clock takes us into the house to capture the stark differences between their songs, with the mechanism of the cuckoo clock represented in the piano part. Lullaby presents a challenge for the players with its delicate unison scoring and exactness of tempo to produce the impression of a mother singing to her child.

A cricket, for all its brevity, effectively mimics the subtle sound heard through an open window. Moonlight through the window carries the nocturnal scene further before one of the most imaginative passages of all Enescu’s writing, Wind in the chimney. This, however, is just the prelude to Storm outside, in the night which follows without a break. It gathers pace and ferocious energy before breaking into the climactic closing Sunrise, which Enescu intends not only as a literal representation but as a vision of destiny, pulling him away from his past back, to the present, and towards a future that cannot be escaped.

Brahms’s third violin sonata is the only one written in four movements. Completed during his summer holiday in 1888 at Lake Thun north of the Swiss Alps, the work is dedicated to the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow.

As with the earlier sonatas Brahms sets the atmosphere in the opening bars, finding an almost symphonic sense of scale combined with the heroic passion of his youthful piano sonatas.

The violin part opens with a sinuous theme, the full intensity of which is only suggested at first. A seeming lack of natural rhythm is further heightened by the sforzandos on the weak beats and the piano’s right hand syncopation.

The heart of the movement is the development section, which is built entirely over a pedalled fifth which seems in constant contrast to the shifting harmonics played over it.

The second movement Adagio in D major provides the only escape from minor keys but maintains its intensity by largely confining itself to the lower and middle registers. The third movement is more openly playful and nervous, despite its brevity.

The final Presto agitato gives the work a sense of balance, as it counterpoints the passion of the first movement by presenting an argument of conflicting emotions, with the exuberant first theme neatly foiled by the more tranquil material of the second theme. Schoenberg later credited this movement as being the inspiration for him to invent the twelve-tone system, such is the feeling of free association between the thematic material.

The Impromptu Concertant is one of several short concert pieces that Enescu wrote for a variety of instruments throughout his life. Dating from 1903, the effusiveness of Enescu’s youthful style is undeniably a major feature of the piece. That it was published posthumously in 1958 also tells us something of Enescu’s self-criticism regarding even the smallest elements of his oeuvre.

The character of this spontaneous work is captured in the eloquent instruction that prefaces the music, “chaleureux et mouvementé”, with tenderness and moving. Its two connected and distinctive parts enable audiences to appreciate the main influences on Enescu’s compositional development. The first part finds both instruments intertwining their lines in a very Viennese manner that reminds at times of Richard Strauss’s lyricism whilst maintaining a sense of airy freedom. The second part is one of passionate expression for the violin against an accompaniment that draws upon Fauré without negating the influence of Brahms in the prominence given to its chord-based construction.

It is known that Brahms destroyed at least three outlines for violin sonatas before completing the three that finally came into being. The Scherzo from the “F.A.E.” sonata is a survivor from his early attempts at grappling with the form. Rather unusually Brahms wrote the Scherzo in 1853 as a contribution towards a collaborative sonata with the composer Robert Schumann and his pupil Albert Dietrich providing the other movements.

It was Schumann who suggested it be dedicated to the violinist Joseph Joachim. As a further source of amusement the composers kept their identities hidden from Joachim until after he had played through the work, which he did in the Schumann household with Clara Schumann at the piano, and guessed their identities without any difficulty.

The work was unpublished in its entirety during the composers' lifetimes, though Schumann incorporated his two movements into his third violin sonata. Joachim retained the original manuscript, from which he allowed just Brahms’s scherzo to be published in 1906.

This is the only part to have maintained its place in the regular repertoire. As a side note of interest, all three composers wrote a concerto dedicated to Joachim.

“F.A.E.” refers to Joachim’s overtly Romantic personal motto, “Frei aber Einsam” (Free but alone), indicating the solitary lifestyle of the virtuoso artist. Dietrich and Schumann both used the notes F, A and E as integral elements of their themes, but Brahms cast his Scherzo in the somewhat removed key of C minor which lends the writing a sense of uncertainty before leading to a coda in C major, which in turn references A minor, the key of the other movements.

Enescu’s third violin sonata is one of his best-known works. As the subtitle “in Romanian Folk Character” indicates, the work provides a unique distillation of Romanian folk music. Enescu was clear about the specific use of the word ‘character’: “I don’t use the word ‘style’ because that implies something made or artificial, whereas ‘character’ suggests something given and natural. The use of folk material does not ensure authentic folk character, it contributes to it when done with the spirit of the people … and in this way Romanian composers will be able to write authentic music but achieve it through different and personal means.” Rather more personally he stated, “I was born rooted in the earth, in ground full of tales and legends. My whole life took place under the influence of my childhood gods.”

The music reflects both Romania’s history and geographic location as a meeting point between East and West, with the absorption over many years of ingredients from the Hungarian, Slavic, Arabic and Jewish traditions as well as native folk forms. Yehudi Menuhin, Enescu’s pupil, referred to the sonata’s sense of “nostalgia, yearning, resignation and intense sadness”, though its bitter-sweet tinge is best captured in the Romanian word dor.

The first movement, marked Moderato malinconico, immediately brings to mind the spirit of a Romanian doina, through the use of parlando rubato playing which imitates free recitative. Here, as elsewhere, this is achieved by a veritable minefield of markings in the score that the players have to negotiate: precise fingerings, several flavours of glissandi, varied harmonics and minute tempo changes every bar or two.

The pianist Alfred Cortot, who accompanied Enescu in the sonata, characterised the second movement as “evoking the sounds of mysterious summer nights in Romania; down below, the silent, endless, neglected plains; above, stars leading into the infinite…” Indeed, aside from Bartók’s use of night music in his chamber and orchestral works, this is the most stunning example of musical imagination that exists in the duo repertoire. The closing movement builds into a wild dance full of rhapsodic reminiscences further heightened and tinged by the doina form before reaching an exultant end.

Programme notes: Evan Dickerson

Violinist Remus Azoitei has achieved international acclaim since his concert debut at the age of eight. Since then, he has performed extensively as a soloist with all the major orchestras in Romania, as well as being a featured soloist with other ensembles in Europe, North America and Japan. Hailed as “an uninhibited virtuoso, with soul and fabulous technique” by The Strad, Remus held a full scholarship to study with Itzhak Perlman and Dorothy DeLay at the Juilliard School in New York, where he obtained his Master’s Degree, as well as studying under Maurice Hasson at the Royal Academy of Music in London.

As a recitalist, Remus Azoitei has performed in venues such as the Alice Tully Hall at the Lincoln Center and CAMI Hall (New York), St-Martin-in-the-fields and Wigmore Hall (London), also appearing, among others, at the Music Festivals of Yokosuka, Cambridge, London, Heidelberg, Paris, Santander, Munich and Bucharest. Remus’ works have been broadcast on the Romanian Cultural Channel, BBC Radio 4, Radio Kishinev, as well as on Concert FM in New Zealand. He has worked with artists such as David Geringas, Nigel Kennedy, Gérard Caussé, Adrian Brendel and Konstantin Lifschitz. After his London Wigmore Hall debut in 2004, the Sunday Express wrote that “he delivered a memorable programme in front of a packed Wigmore Hall, and had the crowd cheering. He is one fine musician.” In 2005, he performed the Bach Double concerto with Nigel Kennedy, a concert broadcast by 19 TV and Radio stations across Europe and North America, including Arte and Mezzo. He has recorded for the Electrecord, Radio Bremen, and Hanssler Classics. At the 2009 Enescu Festival, Remus will be a soloist of the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, conducted by Dmitri Kitaenko.

Remus is a prize-winner at international violin competitions in Milan, Weimar, Bucharest and Wellington. In 2005 he received “The Cultural Order”, a decoration awarded by the Romanian President to him for his musical achievements.

In addition to his busy concert schedule, Remus is dedicated to teaching. He was appointed violin professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London in 2001, becoming the youngest ever violin professor in the history of the institution. In 2006, Remus was awarded the title of Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, ARAM. He is the founder of the Enescu Society in London, as well as its Artistic Director. Tonight, he plays on a 1718 Antonio Stradivari violin, the “Maurin”, kindly offered to him for this concert by the Royal Academy of Music.

Violinist Remus Azoitei has achieved international acclaim since his concert debut at the age of eight. Since then, he has performed extensively as a soloist with all the major orchestras in Romania, as well as being a featured soloist with other ensembles in Europe, North America and Japan. Hailed as “an uninhibited virtuoso, with soul and fabulous technique” by The Strad, Remus held a full scholarship to study with Itzhak Perlman and Dorothy DeLay at the Juilliard School in New York, where he obtained his Master’s Degree, as well as studying under Maurice Hasson at the Royal Academy of Music in London.

As a recitalist, Remus Azoitei has performed in venues such as the Alice Tully Hall at the Lincoln Center and CAMI Hall (New York), St-Martin-in-the-fields and Wigmore Hall (London), also appearing, among others, at the Music Festivals of Yokosuka, Cambridge, London, Heidelberg, Paris, Santander, Munich and Bucharest. Remus’ works have been broadcast on the Romanian Cultural Channel, BBC Radio 4, Radio Kishinev, as well as on Concert FM in New Zealand. He has worked with artists such as David Geringas, Nigel Kennedy, Gérard Caussé, Adrian Brendel and Konstantin Lifschitz. After his London Wigmore Hall debut in 2004, the Sunday Express wrote that “he delivered a memorable programme in front of a packed Wigmore Hall, and had the crowd cheering. He is one fine musician.” In 2005, he performed the Bach Double concerto with Nigel Kennedy, a concert broadcast by 19 TV and Radio stations across Europe and North America, including Arte and Mezzo. He has recorded for the Electrecord, Radio Bremen, and Hanssler Classics. At the 2009 Enescu Festival, Remus will be a soloist of the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, conducted by Dmitri Kitaenko.

Remus is a prize-winner at international violin competitions in Milan, Weimar, Bucharest and Wellington. In 2005 he received “The Cultural Order”, a decoration awarded by the Romanian President to him for his musical achievements.

In addition to his busy concert schedule, Remus is dedicated to teaching. He was appointed violin professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London in 2001, becoming the youngest ever violin professor in the history of the institution. In 2006, Remus was awarded the title of Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, ARAM. He is the founder of the Enescu Society in London, as well as its Artistic Director. Tonight, he plays on a 1718 Antonio Stradivari violin, the “Maurin”, kindly offered to him for this concert by the Royal Academy of Music.

Hailed as an “enormously sensitive pianist with an extraordinary flexible culture of touch, perfect technique as well as a great understanding of music” by the German Weserkurier, Romanian-born Eduard Stan moved to Germany in 1978 at the age of eleven.

After Karl-Heinz Kämmerling noticed his talent, it was Arie Vardi who became Eduard’s main mentor at the Academy of Music and Drama in Hanover, where he obtained his Master’s Degree. Praised by Vardi as “a successful combination of a Romanian soul with musical sensitivity grown on German spiritual ground”, he also benefited from the advice of Herbert Blomstedt, Matthias Goerne, Karl Engel, Boris Berman and Paul Badura-Skoda.

A top prize-winner at international competitions in Cologne, Hamburg and Brunswick, Eduard Stan has appeared at festivals including Massenet (France), Mid-Europe (The Czech Republic), Bourglinster (Luxemburg), Brunswick Classix (Germany) and the Festival of Romanian Music (Romania). He has performed across Europe and the US, including major concerts at the Berlin Philharmonie, Musikhalle Hamburg, Salt Lake City Temple Square and PUC California.

As featured soloist with orchestras in Germany, Austria, Italy and Romania, he performed under baton of Shinya Ozaki, Lutz Köhler, George Balan and Thomas Dorsch, among others. As a sought-after chamber musician revealing “a fine gift of restraint and an instinctive feel for balance” (The Strad), Eduard regularly performs with violinist Remus Azoitei, cellist Laura Buruiana, as well as the Voces and Ad Libitum string quartets, Romania’s leading ensembles.

His affinity for Lied accompaniment is appreciated by singers such as Britta Stallmeister, Sylvia Bleimund, Eliseda Dumitru and Johannes Gaubitz.

Eduard Stan’s critically acclaimed Solo-CDs for Hänssler Classic range from Bach to Debussy. Together with his compatriot Remus Azoitei, he recorded the entire repertoire for violin and piano by George Enescu, a world premiere project coming in two CD volumes, released by Hänssler in 2007.

Eduard Stan has been a teacher at the Lübeck Academy of Music from 2000-2007. As the founder and artistic director of the Enescu-Festival Heidelberg/Mannheim, he was awarded in 2005 the Enescu Medal from the Romanian Cultural Institute for his merits as a promoter of Enescu’s music. Future projects include his debut at Flagey Hall in Bruxelles, the Philharmonie in Luxemburg, as well as a tour Australia and New Zealand in 2009.

Hailed as an “enormously sensitive pianist with an extraordinary flexible culture of touch, perfect technique as well as a great understanding of music” by the German Weserkurier, Romanian-born Eduard Stan moved to Germany in 1978 at the age of eleven.

After Karl-Heinz Kämmerling noticed his talent, it was Arie Vardi who became Eduard’s main mentor at the Academy of Music and Drama in Hanover, where he obtained his Master’s Degree. Praised by Vardi as “a successful combination of a Romanian soul with musical sensitivity grown on German spiritual ground”, he also benefited from the advice of Herbert Blomstedt, Matthias Goerne, Karl Engel, Boris Berman and Paul Badura-Skoda.

A top prize-winner at international competitions in Cologne, Hamburg and Brunswick, Eduard Stan has appeared at festivals including Massenet (France), Mid-Europe (The Czech Republic), Bourglinster (Luxemburg), Brunswick Classix (Germany) and the Festival of Romanian Music (Romania). He has performed across Europe and the US, including major concerts at the Berlin Philharmonie, Musikhalle Hamburg, Salt Lake City Temple Square and PUC California.

As featured soloist with orchestras in Germany, Austria, Italy and Romania, he performed under baton of Shinya Ozaki, Lutz Köhler, George Balan and Thomas Dorsch, among others. As a sought-after chamber musician revealing “a fine gift of restraint and an instinctive feel for balance” (The Strad), Eduard regularly performs with violinist Remus Azoitei, cellist Laura Buruiana, as well as the Voces and Ad Libitum string quartets, Romania’s leading ensembles.

His affinity for Lied accompaniment is appreciated by singers such as Britta Stallmeister, Sylvia Bleimund, Eliseda Dumitru and Johannes Gaubitz.

Eduard Stan’s critically acclaimed Solo-CDs for Hänssler Classic range from Bach to Debussy. Together with his compatriot Remus Azoitei, he recorded the entire repertoire for violin and piano by George Enescu, a world premiere project coming in two CD volumes, released by Hänssler in 2007.

Eduard Stan has been a teacher at the Lübeck Academy of Music from 2000-2007. As the founder and artistic director of the Enescu-Festival Heidelberg/Mannheim, he was awarded in 2005 the Enescu Medal from the Romanian Cultural Institute for his merits as a promoter of Enescu’s music. Future projects include his debut at Flagey Hall in Bruxelles, the Philharmonie in Luxemburg, as well as a tour Australia and New Zealand in 2009.